Observational Learning (Modelling)

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Define observational learning

Discuss the steps in the Modelling process

Explain the prosocial and antisocial effects of observational learning

Previous sections of this chapter focused on classical and operant conditioning, which are forms of associative learning. In observational learning, we learn by watching others and then imitating, or Modelling, what they do or say. The individuals performing the imitated behaviour are called models. Research suggests that this imitative learning involves a specific type of neuron, called a mirror neuron [1][2][3].

Humans and other animals are capable of observational learning. As you will see, the phrase “monkey see, monkey do” really is accurate ([link]). The same could be said about other animals. For example, in a study of social learning in chimpanzees, researchers gave juice boxes with straws to two groups of captive chimpanzees. The first group dipped the straw into the juice box, and then sucked on the small amount of juice at the end of the straw. The second group sucked through the straw directly, getting much more juice. When the first group, “the dippers,” observed the second group, “the suckers,” what do you think happened? All of the “dippers” in the first group switched to sucking through the straws directly. By simply observing the other chimps and Modelling their behaviour, they learned that this was a more efficient method of getting juice [4].

Fig. 23 Monkey See, Monkey Do! A photograph shows a person drinking from a water bottle, and a monkey next to the person drinking water from a bottle in the same manner.

Imitation

Imitation is much more obvious in humans, but is imitation really the sincerest form of flattery? Consider Claire’s experience with observational learning. Claire’s nine-year-old son, Jay, was getting into trouble at school and was defiant at home. Claire feared that Jay would end up like her brothers, two of whom were in prison. One day, after yet another bad day at school and another negative note from the teacher, Claire, at her wit’s end, beat her son with a belt to get him to behave. Later that night, as she put her children to bed, Claire witnessed her four-year-old daughter, Anna, take a belt to her teddy bear and whip it. Claire was horrified, realizing that Anna was imitating her mother. It was then that Claire knew she wanted to discipline her children in a different manner.

Cognitive Factors

Like Tolman, whose experiments with rats suggested a cognitive component to learning, psychologist Albert Bandura’s ideas about learning were different from those of strict behaviourists. Bandura and other researchers proposed a brand of behaviourism called social learning theory, which took cognitive processes into account. According to Bandura, pure behaviourism could not explain why learning can take place in the absence of external reinforcement. He felt that internal mental states must also have a role in learning and that observational learning involves much more than imitation. In imitation, a person simply copies what the model does. Observational learning is much more complex. According to Lefrançois (2012) there are several ways that observational learning can occur:

You learn a new response. After watching your coworker get chewed out by your boss for coming in late, you start leaving home 10 minutes earlier so that you won’t be late.

You choose whether or not to imitate the model depending on what you saw happen to the model. Remember Julian and his father? When learning to surf, Julian might watch how his father pops up successfully on his surfboard and then attempt to do the same thing. On the other hand, Julian might learn not to touch a hot stove after watching his father get burned on a stove.

You learn a general rule that you can apply to other situations.

Types of Models: Live, verbal and symbolic

Bandura identified three kinds of models: live, verbal, and symbolic.

A live model demonstrates a behaviour in person, as when Ben stood up on his surfboard so that Julian could see how he did it.

A verbal instructional model does not perform the behaviour, but instead explains or describes the behaviour, as when a soccer coach tells his young players to kick the ball with the side of the foot, not with the toe.

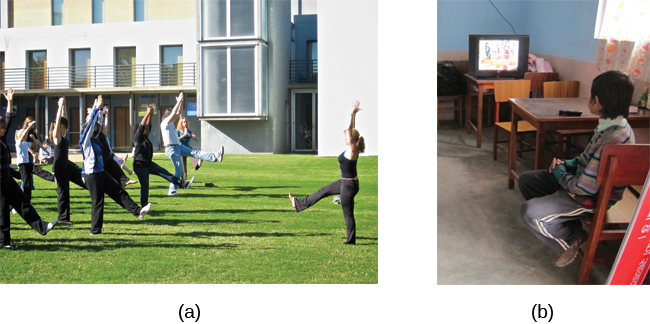

A symbolic model can be fictional characters or real people who demonstrate behaviors in books, movies, television shows, video games, or Internet sources ([link]).

Fig. 24 Photograph A shows a yoga instructor demonstrating a yoga pose while a group of students observes her and copies the pose. Photo B shows a child watching television.

See also

Latent learning and Modelling are used all the time in the world of marketing and advertising. This commercial played for months across the New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut areas, Derek Jeter, an award-winning baseball player for the New York Yankees, is advertising a Ford. The commercial aired in a part of the country where Jeter is an incredibly well-known athlete. He is wealthy, and considered very loyal and good looking. What message are the advertisers sending by having him featured in the ad? How effective do you think it is?

Steps In The Modelling Process

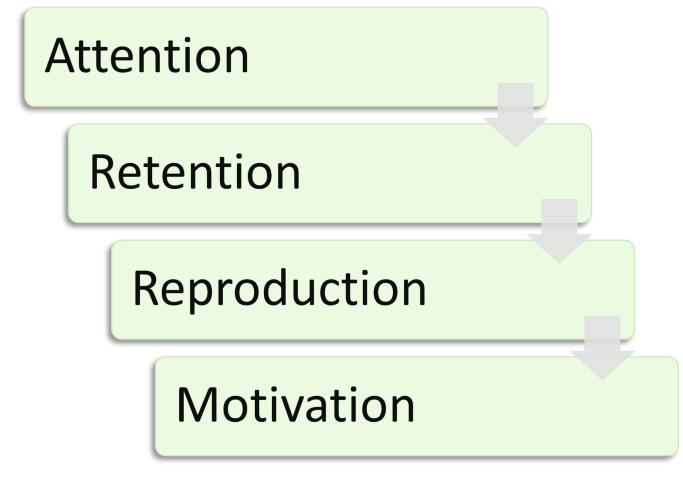

Of course, we don’t learn a behaviour simply by observing a model. Bandura described specific steps in the process of Modelling that must be followed if learning is to be successful: attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation:

First, you must be focused on what the model is doing—you have to pay attention.

Next, you must be able to retain, or remember, what you observed; this is retention.

Then, you must be able to perform the behaviour that you observed and committed to memory; this is reproduction.

Finally, you must have motivation.

Fig. 25 An illustration that shows the four steps in observational learning.

Bandura described specific steps in the process of Modelling that must be followed if learning is to be successful: attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation

Vicarious reinforcement

You need to want to copy the behaviour, and whether or not you are motivated depends on what happened to the model. If you saw that the model was reinforced for her behaviour, you will be more motivated to copy her. This is known as vicarious reinforcement.

Clinical Correlate: Application of vicarious reinforcement

Vicarious reinforcement may be employed in behaviour therapies for children. A sibling can be rewarded for a desirable behaviour while the child under treatment is observing. The reward must be appropriate, eg, praise, and not likely to trigger a tantrum.

Vicarious punishment

On the other hand, if you observed the model being punished, you would be less motivated to copy her. This is called vicarious punishment. For example, imagine that four-year-old Allison watched her older sister Kaitlyn playing in their mother’s makeup, and then saw Kaitlyn get a time out when their mother came in. After their mother left the room, Allison was tempted to play in the make-up, but she did not want to get a time-out from her mother. What do you think she did? Once you actually demonstrate the new behaviour, the reinforcement you receive plays a part in whether or not you will repeat the behaviour.

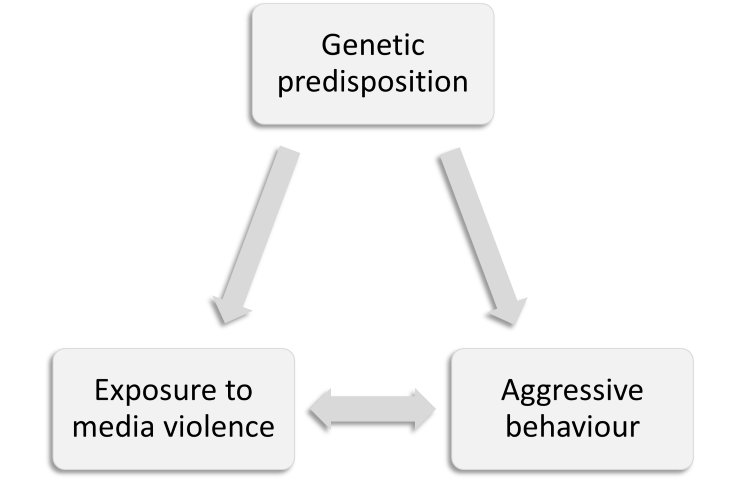

Modelling of aggression and violence

Bandura researched Modelling behaviour, particularly children’s Modelling of adults’ aggressive and violent behaviors [5]. He conducted an experiment with a five-foot inflatable doll that he called a Bobo doll. In the experiment, children’s aggressive behaviour was influenced by whether the teacher was punished for her behaviour. In one scenario, a teacher acted aggressively with the doll, hitting, throwing, and even punching the doll, while a child watched. There were two types of responses by the children to the teacher’s behaviour. When the teacher was punished for her bad behaviour, the children decreased their tendency to act as she had. When the teacher was praised or ignored (and not punished for her behaviour), the children imitated what she did, and even what she said. They punched, kicked, and yelled at the doll.

See also

Watch this video clip to see a portion of the famous Bobo doll experiment, including an interview with Albert Bandura.

Implications

What are the implications of this study? Bandura concluded that we watch and learn, and that this learning can have both prosocial and antisocial effects.

References

Copyright Notice

This work is (being) adapted from on OpenStax Psychology 2e which is licensed under creative commons attribution 4.0 license. We license our work under a similar license. If you copy, adapt, remix or build up on work, you must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.